There was only one other person waiting to see the witch doctor. Like me, he had made the 70km journey from Dar es Salaam. Unlike me, he was looking for a spell. I wondered what problem had brought him all the way down this dirt track, to this village arriving in this small neat courtyard. What was it that only a witch doctor could help him with?

He was in his fifties, tall and gaunt, dressed in the clean red t-shirt and jeans, sporting a greying goatee and a pair of dark glasses. He was an educated man, well-spoken with good English. When I first saw him sitting in the courtyard I had wondered whether he was the witch doctor himself. He certainly looked old and thin enough.

Ali, the boy I’d picked up on the beach 20 minutes earlier, wasn’t giving me any clues. He sat down on a low wall and said nothing. I followed his lead. The courtyard was clean and bright. The day’s washing cast shadows on the neatly painted walls. A single palm tree and a crudely made tin awning provided the only shade from the unrelenting sun. Two scrawny chickens scratched around in the dirt.

The door to the witch doctor’s hut was open. What would I find when I walked into that dark room? Who was in there right now? What was the witch doctor doing for them? Red t-shirt man and I had a whispered conversation. He was not the type of person I imagined would use a witch doctor but I had been warned by my friends in Dar es Salaam, to expect professional people, even politicians to be there seeking advice.

Many people in Tanzania believe that witchcraft can cure ailments such as chronic illnesses, reproductive problems and malaria and as well as a quick fix to business difficulties, infidelity and matters of the heart.

Just as I was contemplating this, there was movement in the doorway. I looked up to see a smiling well-dressed couple emerge from the darkness. They looked at me, greeted me in Swahili and left the courtyard. Red t-shirt man was next. He stood up and made for the door, took his shoes off and disappeared inside. I waited.

My mind went back to the event which had brought me to this place – the message in a bottle l’d found on the beach. I hadn’t been in Dar es Salaam long. I’d got fed up of Uganda, the endless demands for money from beggars and NGOs. The theft of my very expensive laptop hadn’t endeared me the place either. I decided to take my chances in Tanzania instead. I packed my bag, hopped on a plane to Kilimanjaro and made my way slowly eastwards to Dar es Salaam.

Here I had managed to find myself an affordable place to stay on the beach and set about looking for work. On one of my morning walks along the beach I spotted a small brown medicine bottle lying on the sand and bending down to get a better look, to my great surprise, could see a note inside.

Oh the excitement! I would wait until my housemates got back from school and work and we would open the bottle together. I started doing some research. I googled the oldest ever message in a bottle, watched YouTube videos of people opening messages in bottles.

I had visions of TV reporters turning up at my door, the author of the note would be tracked down following a Facebook campaign and then flown halfway across the world to see me in Tanzania. We would walk the beach where it was found and gaze out to sea at the enormity of the journey of that little brown bottle. I would need to get my hair cut, iron some clothes, put on some make-up.

We assembled on the beach and I found a dry patch of sand. I set up my iPhone on a tripod and started filming the opening of what would become the most famous message in a bottle ever found. I gently opened the bottle, tipped out some liquid and teased out a water-soaked note.

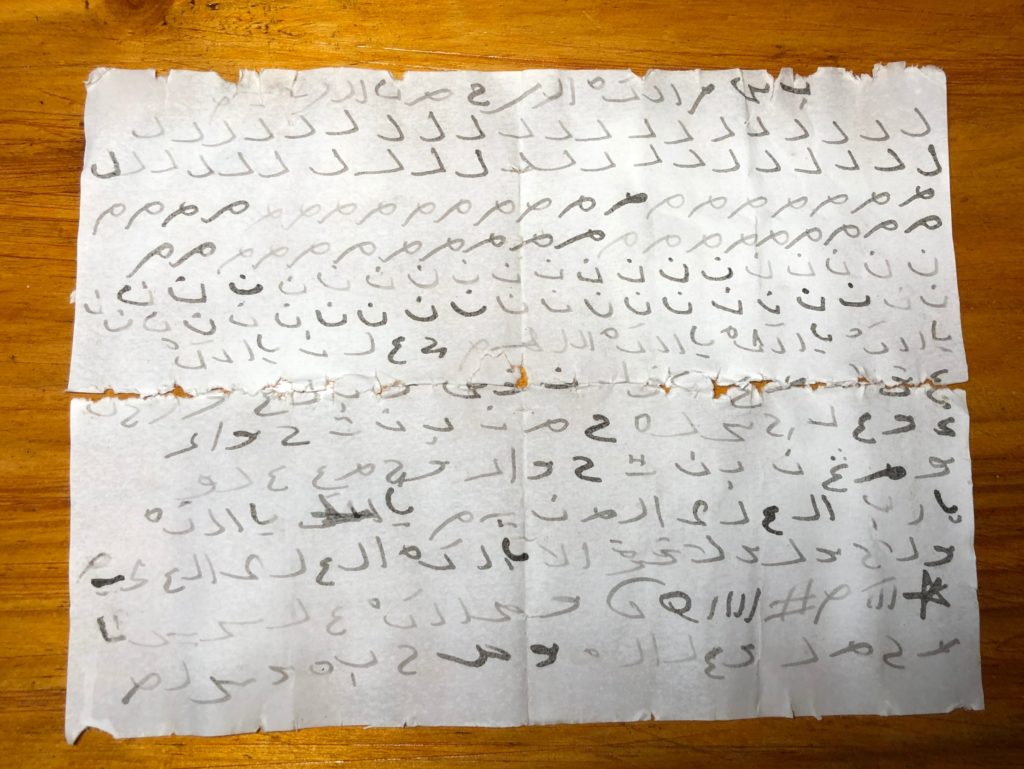

I carefully unfolded it. One of the children said “It looks like someone’s math homework”. It was Arabic script and none of us could make sense of it so I took a photo of the note and sent it to my Egyptian friends. I didn’t have to wait long before my phone pinged. < It looks like a child’s Arabic homework. It makes no sense. There are no words or sentences, just letters > .

Deflated, we all trudged back to the house and I put the note away in a drawer. Several weeks later at a party, I was retelling the story to a local man and he asked to see a picture of the note. “That’s not homework.” he said, “That’s the work of a witch doctor. You need to go to Bagamoyo if you want to find the man who wrote it. That’s where they all are.”.

As luck would have it, I had already planned to go to Bagamoyo the following day and armed with the photo of the bottle and the note, I squeezed myself into a dala dala bus and two sweaty hours later I was tipped out in a dusty crowded bus station.

Bagamoyo is best known internationally as being the former capital of German East Africa and an important staging post for the slave and ivory trade. Domestically it’s better known for the witch doctor trade. I walked along the beach and tried to imagine the days when slaves were shackled and loaded onto boats. I looked at the faces of the fishermen and imagined a different life for them had they been on that beach two centuries earlier.

I abandoned my original plans to get lunch in town. I was impatient to find the witch doctor and flagged down a bajaj (tuk tuk).

It took fifteen bone-crunching minutes along a potholed road to get to the village and then another fifteen minutes bumping along farm tracks, through fields and ultimately back to the village where we had started. When the driver eventually admitted he had no idea where the witch doctor lived I handed over a small bundle of notes and dismissed him. What I needed was a local. I walked down a dirt track to the beach and that’s where I found Ali, standing chatting to a man who was fixing a fishing boat.

Ali is the child of two beggars who had somehow managed to scrape enough money to send their son to school. He was 19 years old, jobless with a friendly disposition and an eagerness to help. His English was poor but good enough for my purposes. More importantly he said he knew where to find the witch doctor.

He led me up from the beach to the centre of the village and the boda boda stand where we selected the strongest looking motorbike. Groaning under our combined weight, the bike took a slow, painful and ultimately circuitous route back to the boda boda stand. Fearing this was another wild goose chase, designed to do nothing more than loosen my purse strings, I looked at Ali. Sensing my confusion he announced “The witch doctor is here.” Still suspicious I climbed off the bike and reluctantly paid the driver. “Follow me.” Ali said pointing to a gap in a wall. And that’s how we’d ended up in this courtyard.

Red t-shirt man ducked as he came out of the hut and before he had the chance to put his shoes back on, I asked him whether he would translate for me. I removed my shoes, took a deep breath and entered.

He sat beneath a small dirty window, wearing a loose blue vest and a traditional Islamic kufi on his head. He was overdue a shave. He looked impassively at me. If he was surprised to see a middle-aged white woman in his hut, he certainly didn’t show it.

When my eyes became accustomed to the darkness I could see he was surrounded by the curious tools of his trade, a basket full of eggs and twigs, half a pack of A4 paper, small pieces of white paper covered with red Arabic script and a sack of flour. Half a dozen duck eggs lay on a piece of newspaper to my left and in front of me, several small pots of charcoal. In his hands he held a shallow wooden tray with a fine covering of what looked like flour. I tried but failed to lower myself gracefully onto the floor and taking the lead from my new friend, I shuffled myself into a crossed-legged position facing the witch doctor.

When I explained to him that I was looking for an interpretation of the note I had found in the bottle on the beach, he put down the tray. I held up my phone so that he could see the note. He studied the photo in silence, hands resting in his lap. Red t-shirt man and I sat and waited. My arm started to ache.

My friend in Dar es Salaam had told me that these witch doctors have very little formal education but had normally spent some time at a Madrassa (Islamic school) when they were young where they learnt basic Arabic script. Typically, they learn enough to form letters but not enough to form words which explained why the note I had found looked more like a child’s homework than a spell.

He finished studying the note and addressed my interpreter. “It’s a curse,” he said, “a curse on an enemy”. Asked to elaborate on the details of the curse he checked the photo again. “It’s a curse which will bring terrible stomach pains. Bad spirits will enter his body and live in his stomach and when he goes to the hospital for surgery, the doctor will cut him open but nothing will be found inside him.”

He added an insurance policy, “It works in about 75% of cases.” I thanked him for his translation.

His eyes met mine for the first time and he spoke slowly. “You white people are always picking things off the beach. You shouldn’t do this. There are dangerous spells in the bottles and opening them can bring sickness to you and your family.” I nodded, thanked him for his advice and apologised for my ignorance. “Where is the note now?” he asked. On learning that I still had the note in the house he advised me to go home and “Burn the note immediately and throw the bottle back into the sea”.

I had no intention of adding to marine pollution. The Indian Ocean already dumps mountains of 21st century flotsam and jetsam at the bottom of my garden. The note contains nothing more than childish Arabic writing and meaningless squiggles, a placebo for the superstitious and the desperate. It serves as evidence that even today with advanced medical treatment for almost all known diseases, there are still some problems for which the only remedy lies in a small dark hut in a dusty village down a pot-holed track on the coast of Tanzania.

The consultation was over. He agreed to my taking some photographs and I gave him the equivalent of £3 for his advice. I heaved myself back into a standing position, thanked him for his help and emerged from the darkness back into the light.

This little brown bottle with its peculiar message has taken me on a journey of excitement, disappointment, wonder and now the calm waters of satisfaction.

There may be no TV crews beating a path to my door, no viral YouTube video of the grand bottle opening, but I have something more valuable. I have contentment, an end to the mystery and the address of a man who can put a disease in the stomach of the thief in Kampala who stole my laptop.